“It now seems just like a very bad dream which took three years out of our lives, though I cannot say that I didn’t profit from them in greater human understanding and appreciation of life and freedom according to our precepts.”

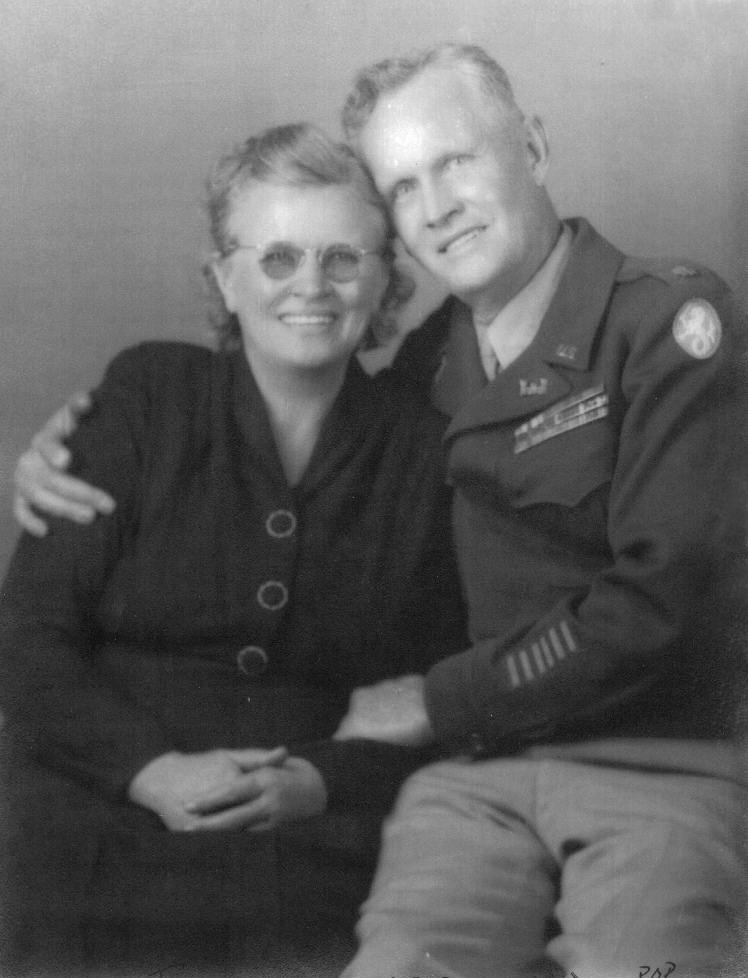

Former Guam resident Gertrude “Trudis Aleman” Constenoble Hornbostel vividly recounted their harrowing experience as prisoners of war of the Japanese at the University of Santo Tomas internment camp in the Philippines during World War II.

The University of Santo Tomas, originally the Royal and Pontifical University of Santo Tomas in Sampaloc, Manila, was converted into an internment camp by the Japanese from 1942 to 1945. Among those detained were prominent expatriates, predominantly Americans and British nationals, alongside individuals of various other nationalities.

Gertrude shared her family’s ordeal in an article she penned for The Star, the monthly publication of the United States Marine Hospital National Leprosarium in Carville, Louisiana. It was during her internment in Manila that she contracted Hansen’s disease. Following a medical examination in San Francisco, she sought treatment at the Carville facility in 1946, where her husband, Major Hans Hornbostel, chose to reside nearby, drawing significant media attention. Through their public presence, the couple contributed to combatting the stigma and misinformation surrounding the disease.

Reflecting on their initial Christmas in Santo Tomas in 1942, Gertrude admitted struggling to recall the specifics amidst the trauma of their captivity. The grim reality of war prisonerhood loomed large, overshadowing any festive spirit.

Accompanied by her children—Earl Henry, Gertrude Hilde (Tootsie), and Johanna Marie—the Hornbostels endured the harsh conditions of Santo Tomas. Johanna would later be transferred to Los Banos camp in Laguna in November 1943, while Earl faced unjust imprisonment after being accused of a crime.

Hans, the family patriarch, enlisted in the U.S. Army at 59 and found himself in Bataan when his family was detained in Santo Tomas. His subsequent survival of cerebral malaria, though concealed from Gertrude until after his recovery, exemplified the resilience of those ensnared in the tumult of war.

As conditions deteriorated within Santo Tomas, Gertrude noted the gradual onset of hardship. Food shortages became acute, and malnutrition ravaged the internees, with beriberi becoming all too common. Emotional distress compounded their physical suffering, exacerbated by the ever-present threat of arbitrary arrest by Japanese authorities.

In 1944, Earl’s arrest by the Kempeitai marked a further descent into uncertainty for the Hornbostels. Outside aid dwindled as the camp’s resources diminished, leaving many to rely on the generosity of fellow internees to survive.

For Gertrude and her family, as for countless others, internment was a test of endurance. Yet amid the adversity, glimpses of humanity endured—small gestures of kindness and resilience that offered solace amidst the turmoil.

The Hornbostels’ saga serves as a poignant reminder of the enduring human spirit in the face of adversity, a testament to the resilience of the human heart even in the darkest of times.

First Christmas at Santo Tomas, 1942

Despite the shadow of captivity, Gertrude recalled a fleeting moment of respite during their initial Christmas in Santo Tomas. A makeshift celebration, marked by modest festivities and gestures of goodwill, offered a brief reprieve from the grim reality of war.

As the war dragged on, however, Santo Tomas became a crucible of suffering, its walls bearing witness to the trials and tribulations of those held captive within. Yet amidst the despair, the indomitable human spirit found ways to prevail, offering hope in the face of adversity.

Discussion about this post