In a pivotal turn of events in 1922, eight years after the establishment of Japan’s naval structure, a mandate demanded a shift towards civilian governance. This transition was embodied by the emergence of the Nanyo Cho (South Seas Government).

Nanyo Cho would wield administrative powers; however, it lacked sovereignty, leaving the local populace vulnerable without the protection of the Meiji Constitution.

Originally headquartered in Chuuk, the Nanyo Cho later relocated its base of operations to Koror in Palau. Governed by a colonial governor vested with executive, judicial, and legislative powers, the Nanyo Cho signaled a significant administrative evolution, symbolized by the construction of the Administration Building on the site once occupied by the German administration in Garapan.

During the early stages of the Nanyo Cho era, there was a modest Chamorro and Carolinian presence on Saipan and Rota, juxtaposed against the uninhabited status of Tinian and the surrounding islands. Economic activities at this time centered around subsistence farming and fishing, with an emphasis on preserving the integrity of the land.

Despite Japanese reservations about immigration, early attempts to establish sugar enterprises lured thousands of Japanese laborers. However, the collapse of the industry left 2,000 workers stranded, highlighting the challenges posed by the unfavorable business climate under the Mandate.

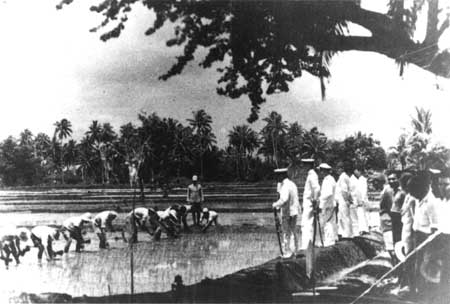

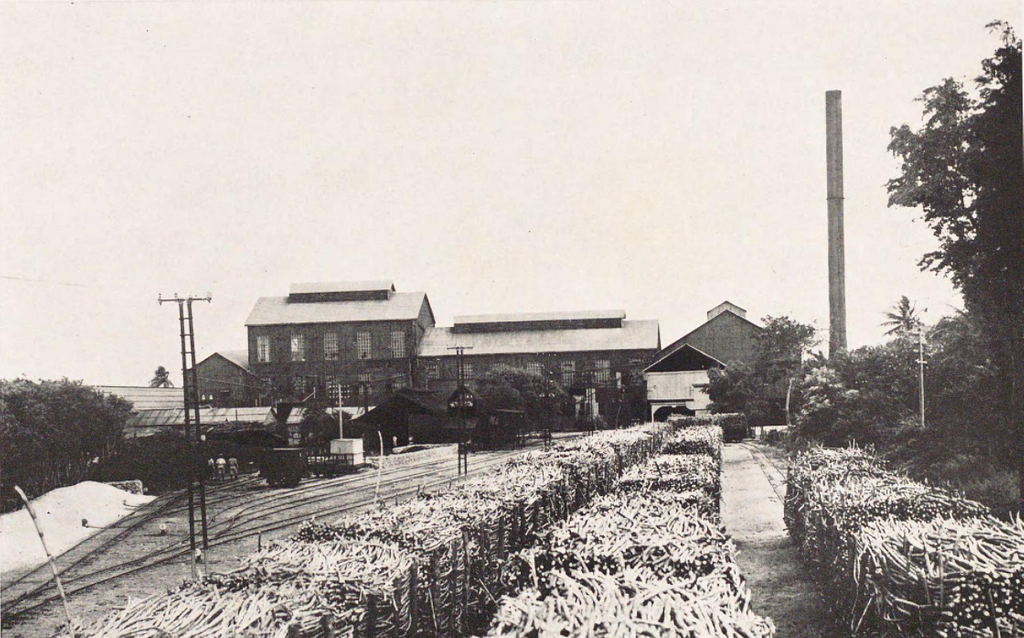

Enter Matsue Haruji, hailed as the “Sugar King,” who revitalized the industry through Nanyo Kohatsu Kaisha (NKK or Nanko). Equipped with a master’s degree from LSU and U.S. experience, Matsue orchestrated a comprehensive overhaul, which included the construction of a narrow-gauge railroad system to facilitate the transportation of sugarcane from plantations to processing mills.

Despite initial setbacks, Matsue’s interventions bore fruit by 1926, with sugar plantations flourishing in Kagman and Laulau, alongside expansions into Tinian, favored for its fertile soil. However, attempts to replicate this success in Rota were thwarted by unsuitable soil conditions.

Beyond sugar, thriving industries such as mining, fishing, and copra production emerged, with Rota emerging as a pivotal mining hub. Economic growth was paralleled by a rise in the indigenous population, accompanied by the development of modern towns and improved living standards. However, these advancements were marred by environmental degradation and the marginalization of local inhabitants.

By the 1930s, the NKK’s heavy reliance on outside labor dramatically altered demographic dynamics, with Japanese nationals outnumbering locals tenfold, leading to the marginalization of indigenous populations. In 1935, Saipan housed 20,280 Japanese nationals (including Japanese, Okinawans, and Koreans), alongside 3,282 Chamorros and a mere 10 Carolinians. Tinian mirrored a similar trend, with 14,208 Japanese nationals compared to just 25 locals, while Rota saw 4,841 Japanese nationals against 764 locals. Only on Pagan did Chamorros slightly outnumber foreigners, with 131 to 89.

This influx of foreign labor marginalized indigenous islanders, relegating them to peripheral roles in the islands’ affairs.

In terms of social hierarchy, the Nanyo Cho era embraced a stratified structure: first rank for Japanese from the home islands, second for Okinawans and Koreans, and third for islanders (known as “Toming”), further subdivided into Chamorros and other Micronesians referred to as “Kanaka”.

Economically, the islands experienced a concurrent rise in living standards, driven by the availability of wage labor, common land leases, and improved healthcare. Villages transformed into towns during the Nanyo Cho Period, including Garapan and Chalan Kanoa on Saipan, Tinian town on Tinian, and Songsong on Rota.

However, economic progress was tempered by environmental repercussions, as extensive deforestation and sugarcane cultivation disrupted ecological balances, leading to pest infestations.

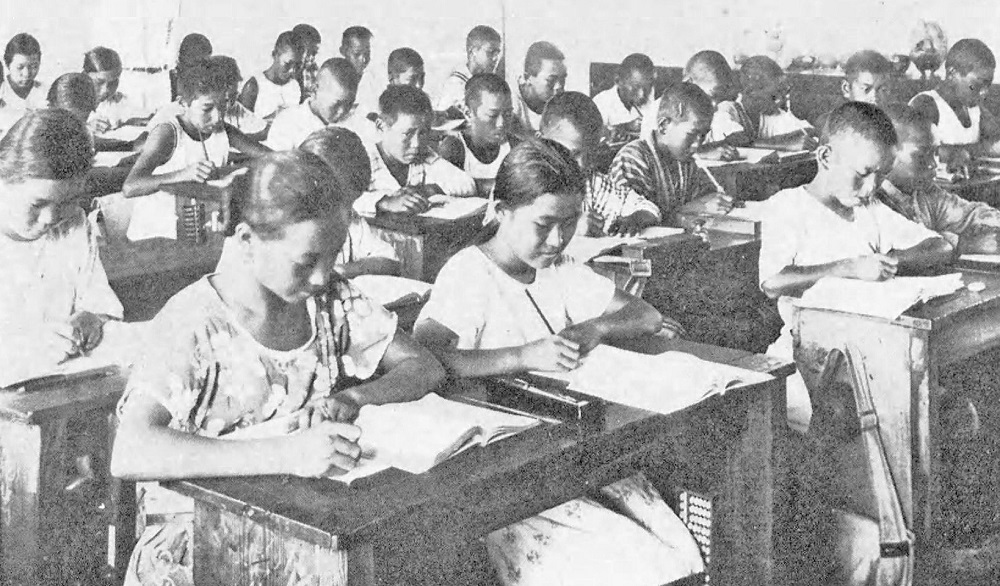

Education during the Japanese Period saw local children attending three-year Kogakko schools, while Japanese counterparts pursued eight-year primary education at Shogakko. Teaching methods emphasized rote learning and discipline, with a focus on Japanese language, moral education, mathematics, geography, gymnastics, and handicrafts.

In matters of religion, the local community predominantly adhered to Roman Catholicism, with the absence of priests from 1914 to 1921 until the arrival of Spanish Jesuits and Mercedarian sisters. Notably, Gregorio Sablan (Kilili), a prominent figure and later Saipan’s first mayor, maintained religious records during this period.

Amidst Japan’s advocacy for militarism and the establishment of Shinto as a state religion, societal dynamics in the Marianas during the Japanese era reflected a complex interplay of colonial influence, socio-economic transformations, and cultural assimilation.

Discussion about this post